Maps of DevOps: The Second Way

Posted on May 19, 2020 in DevOps Updated: May 22, 2020

Welcome

Welcome to the second post in the Maps of DevOps series! In The First Way, we introduced the scenario of mailing letters to use as a stand-in for delivering software and discussed the necessity of performing our analysis from a system perspective. In doing so, we discovered that Single Piece Flow (SPF) was superior to batching because we could more quickly deliver value.

Along the way, we also introduced the map of Known Territory (where we are when we know what we are doing) and alluded to the Unknown (where we are when we don't). In this post, we will discuss the important and ever-present mediator between them - Anomaly.

Anomaly

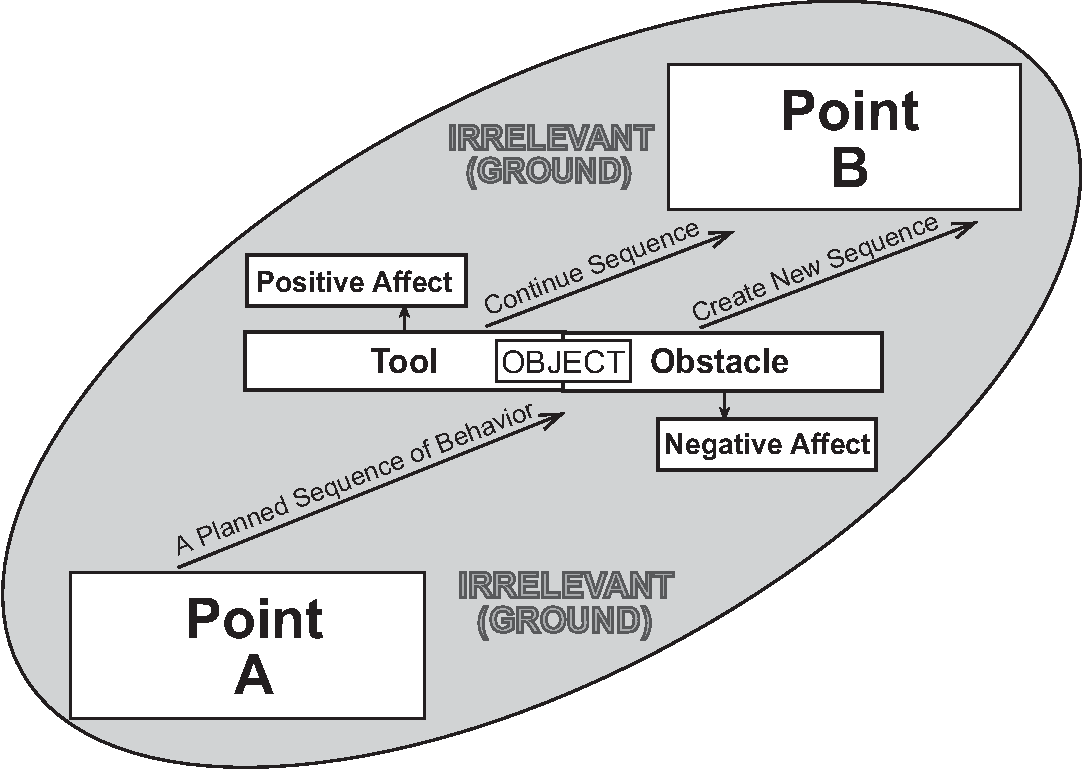

We will define Anomaly as new information that deviates from the expected. This new information can be either positive or negative - that is, it can be either a Tool or an Obstacle. A Tool aids us in reaching the stated objective while an Obstacle hinders our ability to move forward.

Notice that this is a subtle but important move to define tools in terms of their actual outcomes rather than hoped for results. In particular, note that many new technologies are labeled "tools" but may not fit this definition. One cannot "do DevOps" simply by implementing DevOps "tools" - they must address some particular need at hand. This common mistake underlies the trend of "DevOps" becoming simply a marketing gimmick for selling the latest tools and related services.

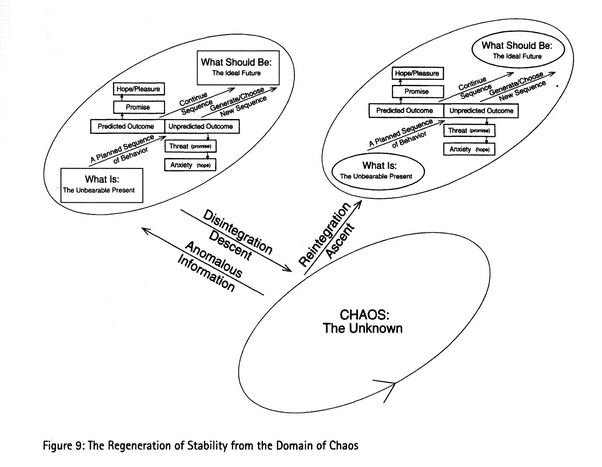

Returning to anomaly, we may be justified in thinking that they are rare events (almost by definition), but the potential for anomaly always surrounds us in latent form. Small enough anomalies may hardly be noticed as we are able to quickly incorporate them into a known map, or schema, within which to understand them. However, a sufficiently large anomaly can transform the Known into Unknown or, as it can well be called, Chaos. We experience this when something so unexpected happens that our current pursuits or methods or even our current state of being come into question.

To illustrate, suppose you are folding papers in our letter mailing scenario and the table catches on fire. You are now in a very different place with very different motivations than you were before! Your previous map has disintegrated, and this new information must be taken into account and reintegrated into a new one (presumably centered around putting out the fire and only sometime afterwards resuming paper folding).

Many will be familiar with the colloquialism of saying a project is "on fire" when a catastrophic problem or situation arises. If this symbolism is not immediately understood it is at least forever remembered: the state of the project needs to be reevaluated and immediately attended to because a foundational assumption has come into question. We have descended into Chaos. In order to carry on, the map we had used to guide us forward must be updated to account for the anomalous information that has come to our attention.

Anomalies in Mailing Letters

To further our analysis, consider the following less extreme anomalies that could occur:

- Letters have gotten too big for their envelopes

- Envelope seals do not hold and open in transit

In the first case, the sealer can communicate this back to the folder. Notice that the issue is greatly relieved by the Single Piece Flow delivery model - we get feedback after only one letter is too large thus minimizing rework. In the Batch strategy, every letter of the batch would need to be refolded. Alternatively, we need bigger envelopes, and it is better to know on the first one rather than having already ordered enough envelopes for the entire batch of paper.

In the second case, this may mean letters are never delivered, and we only find out weeks later through receiving an angry call from the intended recipients. And this only if we are lucky enough for them to be expecting the letter - how many important but unanticipated letters fail to go through? The questions arise:

- How often is the envelope seal not holding?

- Where in the process is the issue occurring?

- When did the issue start?

The answers to these question may determine whether it was a freak accident or a fundamental flaw in our process. Worse still, if we cannot even determine the answers to these questions, we must ask even more fundamental ones, e.g. should we even continue trying to mail letters?

The key to mitigating the first case was the quick feedback we received, and that is exactly what we need now. Perhaps we could monitor the initial seal quality on new envelopes and track letters as they travel to report back on seal status?

The Second Way: Amplify Feedback Loops

What we have discovered is the need for The Second Way. Fundamentally, we are trying to answer two questions (and answer them continually):

- Do we know where we are (What Is)?

- Are we achieving What Should Be?

In other words:

- Are our past hypotheses and assumptions still valid?

- Was our latest business hypothesis correct?

Is the system still functioning the way it should, and if it is not, can we easily look into its current state? Did the change we deployed create the value we expected? When we create a new screen in our application, can we tell if anyone is actually using it? If we modify one piece of the system, does it still process inputs from upstream systems correctly or are there any adverse effects on systems downstream?

How To Use This Info

Notice that there are at least two classes of problems here: ones stemming from changes we produce within and those originating from the environment without.

For changes produced by us, The Second Way goes hand-in-hand with The First. The value in continuous monitoring of the system is decreased if our changes are not continually deployed - the feedback we receive on the impact of our changes is only as continuous as the rate at which we deploy them. Indeed, if many changes are made at once and a problem occurs, it can be very difficult to isolate the contributing factors even if we are quickly alerted of the issue. And if on the other hand we see increased value, it can be hard to tell which of the many changes contributed (so we can continue down that path) and which had no effect (so we can focus our attention elsewhere).

That said, problems arising from the environment are still very susceptible to continuous feedback. Our applications do not exist in a vacuum. They are reliant on the storage and memory capacity of the servers that host them, perhaps on the availability of a database or other service, access to network locations, or any other systems which are assumed to exist for our applications to function properly. This surrounding infrastructure has just as much if not a greater effect on their status than the content of their code. A monitoring system that can alert us of issues at the time they arise - or even before - can be invaluable in keeping a system functional.

Tools of the Trade

Basic monitoring and alerting on the environment can be as easy as writing shell scripts to check how much disk space or memory is left on a server. Indeed, this may be a good place to start if there is nothing in place - the important thing is to gain an understanding of the assumptions of the system in question and thus to get an idea of what needs to be monitored. Remember that a monitoring "tool" that shows metrics you do not understand or know how to correlate to the state of the system is not really a Tool - it is a distraction.

Having said that, shell scripts are not a good long-term solution as they do not easily scale, can become cumbersome to maintain, and put you in a position of reinventing the wheel. That is where Network Monitoring tools such as SolarWinds and Splunk start to shine.

In contrast to environment monitoring, Application Performance Monitoring (APM) solutions are required to get insight into the state of all but trivial applications. These tools work by either attaching to your application's processes in a lightweight manor to monitor its calls or by your adding explicit instrumentation to your code (or both). APM solutions include New Relic and Dynatrace or the Azure service Application Insights.

Service monitoring and observability is a huge topic, so we can only scratch the surface here. However, the key point to keep in mind is that what makes these "tools" into Tools is their ability to help us keep Chaos at bay by giving us feedback in the form of checking our assumptions about the current state of the system and validating that the changes we make create value.

Spotlight: APM

APM strives to detect and diagnose complex application performance problems to maintain an expected level of service -Wikipedia

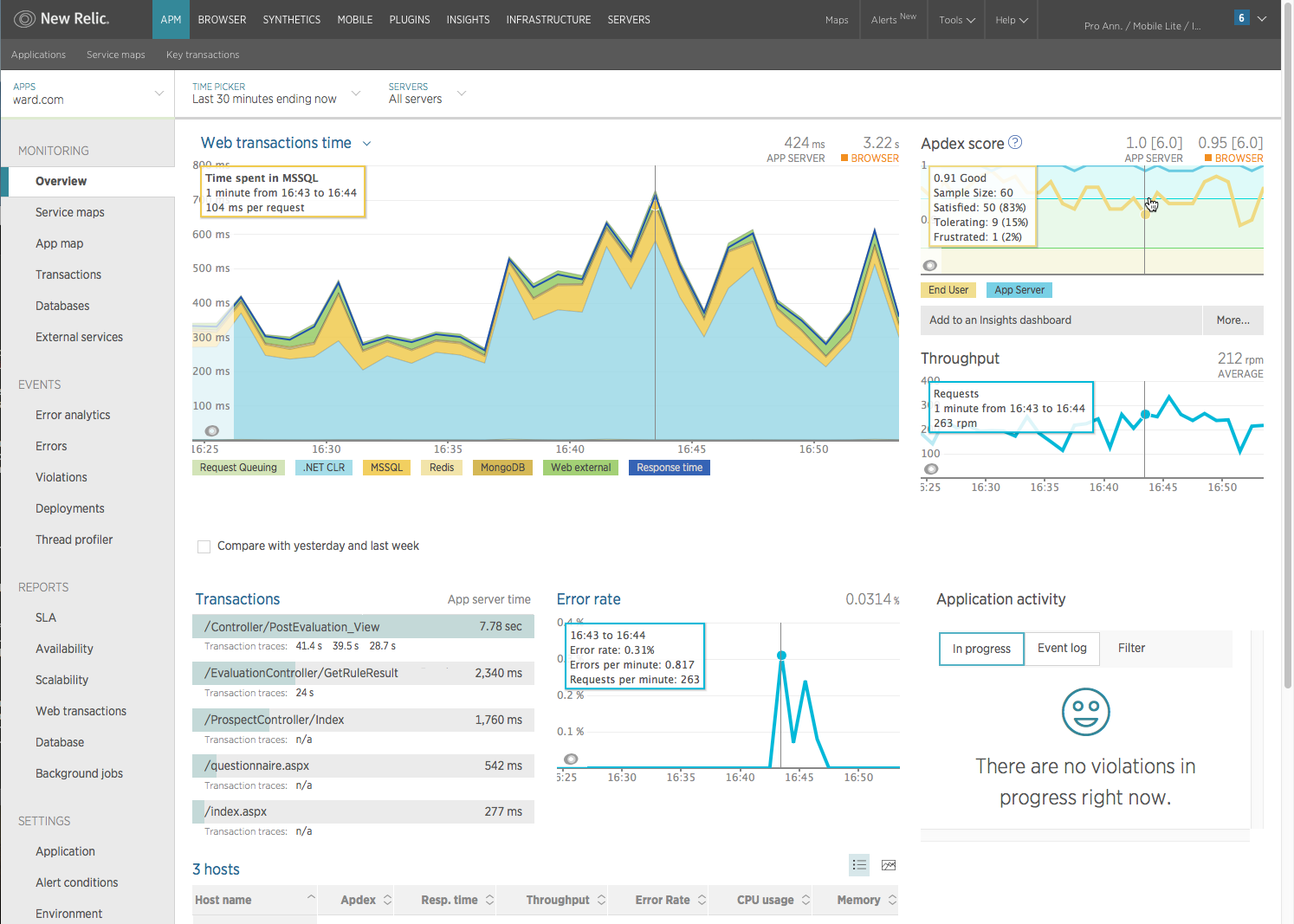

Below is a dashboard view from the application performance monitor New Relic which I single out just because I have experience with it. The sample is for a web application which is a particularly valuable use case for an APM as it can track and break down web response times - the functionality in a website does not matter if it is too sluggish to use.

An APM "[translates] IT metrics into business meaning (value)" writes Larry Dragich. From this snapshot, we can see the response times users are experiencing, where that time is spent, what the longest running transactions are, and more. By knowing this, we are able to make informed decisions about whether or where to spend time optimizing as well as if changes we make have an adverse effect on the user experience or error rate of the application. Getting this feedback before users complain can make all the difference in being able to remediate an issue quickly and users silently abandoning or building resentment of your applications.

References

- Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Jordan B. Peterson (1999), Routledge (BOOK) - https://www.amazon.com/Maps-Meaning-Architecture-Jordan-Peterson/dp/0415922224

- The DevOps Handbook: How to Create World-Class Agility, Reliability, and Security in Technology Organizations; Gene Kim, Patrick Debois, John Willis, Jez Humble, John Allspaw (2016), IT Revolution Press (BOOK) - https://www.amazon.com/DevOps-Handbook-World-Class-Reliability-Organizations/dp/1942788002