Maps of DevOps: The First Way

Posted on December 08, 2019 in DevOps

Welcome

Welcome to the second post in the Maps of DevOps series! In this installment, we will explore The First Way: Systems Thinking.

Motivating Scenario: Mailing Letters

In an attempt to avoid the obfuscating effect of technical jargon, we will use a technology-agnostic scenario as the stage within which to play out our DevOps exploration. The scenario, taken from The DevOps Handbook, is that of mailing letters and will be used throughout the series. The tasks involved are as follows:

- Fold letter

- Insert letter into envelope

- Seal envelope

- Stamp envelope

- Mail letter

We can keep the following possible translation in mind throughout:

| Item | Translation |

|---|---|

| Folder | Development Team |

| Folded Paper | Compiled Code |

| Sealer/Stamper | Operations Team |

| Mailed Letter | Deployed Application |

Where the "development" and "operations" teams can refer to those organizations within a company, to individual developers and operations engineers, or even to the multiple roles a single person can fill. Indeed, how the dynamics change with each of these interpretations is something else to keep in mind.

People in systems do not do what the system says they are doing

-The Functionary's Falsity, John Gall, Systemantics: How Systems Work and Especially How They Fail

One person performing all of these tasks could reasonably be said to be sending letters (i.e. delivering valuable applications). However, once a system is set up and tasks split between people, there are only paper folders (developers writing code) and envelope sealers (operations team deploying binaries). It is now the system which is sending letters and not any individual within it.

The function performed by a system is not operationally identical to the function of the same name performed by a person

-The Operational Fallacy (long form), John Gall, Systemantics

In this light, it is entirely reasonable to imagine - as indeed does happen - that the system is in fact producing mounds of folded paper which either does not fit in or is more numerous than the given size or number of envelopes. Thus, a system operating under this structure may not be sending letters at all. The motivated reader is encouraged to think of other ways in which the system could be doing something entirely different than its stated purpose.

Motivation for Maps

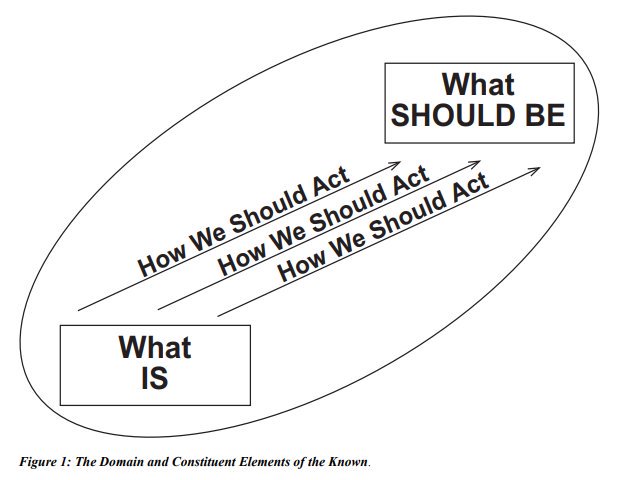

The "maps" after which our series is named refer to constructs out of the book Maps of Meaning. We will first consider the "map" of Known (or Explored) Territory, diagrammatically represented as The Domain and Constituent Elements of the Known. This is the landscape you inhabit when you know what you are doing:

- You exist in the state of What Is

- You aim for What (you believe) Should Be

- You execute a sequence of behavior to move from the former to the latter

Why is it appropriate to call this a map? It is a map in the sense that it describes where you are, where you are going, and how to get there even though those "places" may not be physical. A mental map is no less real simply because it does not take up physical space or guide you to a physical address. Contrast this with Unknown (or Unexplored) Territory: you do not know where you are, what you are doing, or where you need to go (more on this later).

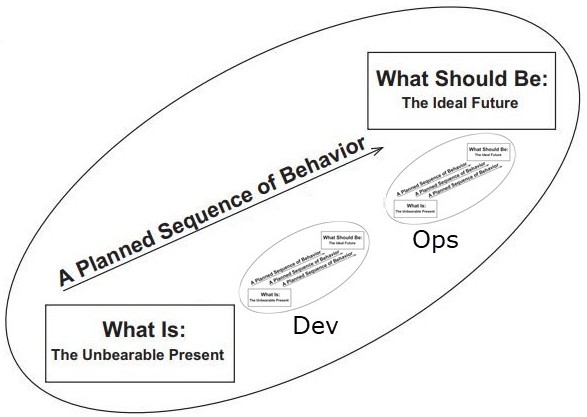

This leads to our first key insight: A business inhabits the same existential landscape. The sequence of behavior has a different content but not a different objective. To represent this, below I have modified The Domain and Constituent Elements of the Known to show the maps of both development and operations embedded within the larger map of the business.

That is to say, a technology firm pursues value through the actions of its Development and Operations organizations. These organizations in turn have their own maps, all the way down to the level of the individual employees (which of course is the level of analysis we started with). As we have previously noted, these maps may not be in alignment. However, seen within the broader perspective of the organization as a whole, this is as undesirable as the proverbial hunter chasing two rabbits at once.

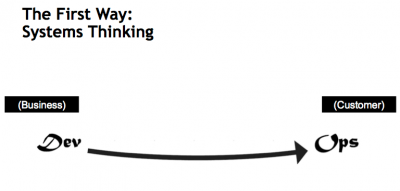

The First Way: Systems Thinking

Stop Starting. Start Finishing.

-David J. Anderson

Applying this framework to our mailing letters scenario, we have:

- What Is: unfolded paper, un-mailed letters

- What Should Be: folded paper, mailed in envelopes

Now the question arises, what sequence of behavior should we pursue?

- Batches: Fold all paper first, insert all papers into envelopes, seal all envelopes, etc.

- Single Piece Flow: Fold a single piece of paper, insert it into an envelope, seal its envelope, etc.

It is easy to see that the Single Piece Flow (SPF) approach achieves What Should Be faster - that is, SPF is the superior way of delivering the value we seek. This is because value is in filled, sealed, mailed envelopes, not folded paper! A development team that produces volumes of untested, undeployed code has not created value.

How To Use This Info

One common and very useful practice to enable Systems Thinking is Value Stream Mapping which involves identifying the series of steps necessary to take a proposed change from conception to final delivery. If you do not know what all of these steps are, who does them, or how long they take, it becomes very difficult - if not impossible - to identify where the constraints are that cause bottlenecks in the system.

Sometimes more importantly, it is also difficult to tell which parts of the process are the most loathsome to those performing them. This point is particularly important if there is not significant buy-in or even active resistance to trying to change existing processes to align more with DevOps principles. Do not underestimate the benefits a boost in morale can confer to the desire people have to contribute to and believe in the potential of a DevOps transformation.

Applying this principle to itself, remember that a DevOps transformation does not need to happen in one batch. Make small, valuable changes (at the constraints and pain points!) and implement them through to the end. This is not a time to let perfect be the enemy of good.

Tools of the Trade

This and the following section are targeted specifically to the domain of software development. Readers unfamiliar with the software development life cycle may skip the remaining content without worry of missing any key concepts.

That said, an in-depth discussion of tooling is beyond the scope of this series given that our focus is primarily on the principles underpinning DevOps. However, we would be remiss not at least to mention along the way some of the more ubiquitous tools to provide the technical reader with avenues for further independent investigation. Tools most related to The First Way are Continuous Integration / Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) Pipelines, examples of which are Azure DevOps or Jenkins (and many others).

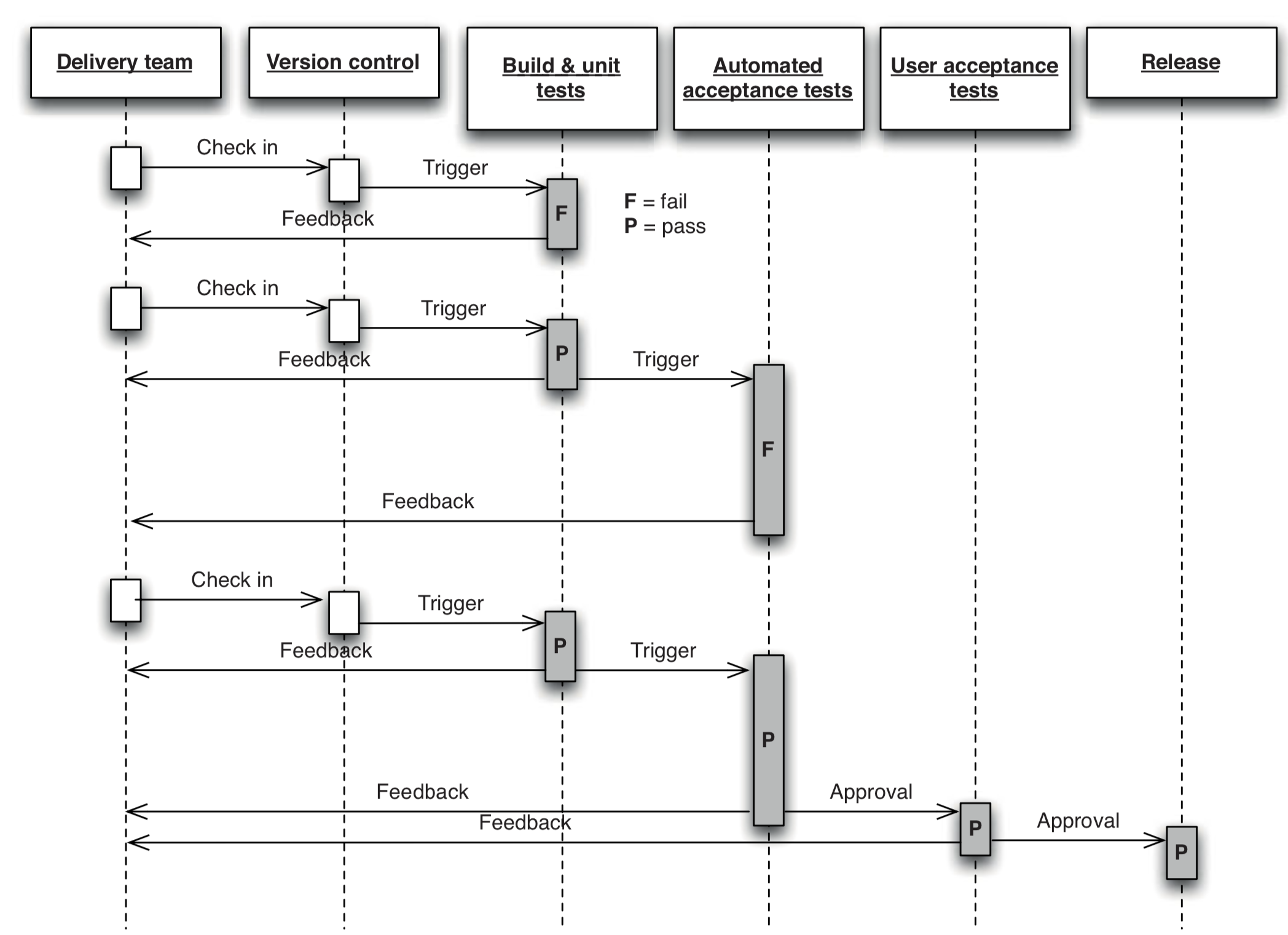

Spotlight: The Deployment Pipeline

The CI/CD Pipeline is an automated process for getting code produced by a developer into the hands of the end user. The following diagram from Continuous Delivery is an abstract representation of that process.

For most technology organizations, the steps required for that process follow the same high-level pattern (or if they don't, they probably should). These steps include checking a change into version control, building an artifact of the code as of that point in time (i.e. a snapshot of the checked-in code whether compiled or otherwise), and the progression of that artifact from cheaper / more volatile environments (sandbox and development) to more expensive / more stable environments (user acceptance testing and production). The CI/CD pipeline provides consistency and visibility to a process that otherwise would be manual (and thus error-prone) and opaque.

For more information, we would encourage interested readers to reference the excellent treatments of the CI/CD pipeline found in Continuous Delivery as well as The DevOps Handbook or simply to query their preferred search engine for the wealth of material online.

References

- Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, Jordan B. Peterson (1999), Routledge (BOOK) - https://www.amazon.com/Maps-Meaning-Architecture-Jordan-Peterson/dp/0415922224

- The DevOps Handbook: How to Create World-Class Agility, Reliability, and Security in Technology Organizations; Gene Kim, Patrick Debois, John Willis, Jez Humble, John Allspaw (2016), IT Revolution Press (BOOK) - https://www.amazon.com/DevOps-Handbook-World-Class-Reliability-Organizations/dp/1942788002

- Continuous Delivery: Reliable Software Releases through Build, Test, and Deployment Automation; Jez Humble, David Farley (2010), Addison-Wesley Professional (BOOK) - https://www.amazon.com/Continuous-Delivery-Deployment-Automation-Addison-Wesley/dp/0321601912

- Systemantics: How Systems Work and Especially How They Fail, John Gall (1977), Quadrangle (BOOK) - https://www.amazon.com/Systemantics-Systems-Work-Especially-They/dp/0812906748